Need to know for non-executive directors and senior management

Welcome to the winter issue of Boardroom Essential, our premium content tailored for non-executive directors and senior management.

If you have any colleagues who would may be interested in our content and like to sign up for our communications, please do email us.

Click on the titles below to jump to the topic you would like to read.

DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION PROJECTS: MANAGING THE RISKS

Whether adopting cloud-based systems, updating legacy infrastructure, or introducing AI and new digital tools, businesses increasingly rely on complex technology and supply chains.

While offering significant benefits, this also introduces new risks. Compatibility issues, software failures, inability to deliver the promised new spec and security vulnerabilities can cause disruption, sometimes on a large scale.

When digital solutions fail the results can be disastrous.

This article looks at the key overarching aspects of: (i) planning and implementing a complex tech transformation project; and (ii) responding effectively if digital solutions fail.

Prevention is better than cure

Effectively managing a complex transformation project requires (among other things) relevant expertise, careful planning, thorough testing and prompt action when issues arise. It will not be a surprise, therefore, that a successful transformation project requires good project management.

In our experience, organisations are, overall, good at putting in place organisational or implementation frameworks designed to support the projects of this kind. Where the problems creep in is how those frameworks are implemented and particularly how they adapt to inevitable changes to the project as it goes along. In this regard, culture and expertise can have a real impact on doing that effectively.

Culture

Successful implementation of a project depends, among other things, on the ability to create a culture where: (i) it is okay to voice concerns and raise problems; and (ii) the IT function feels (and acts) as part of the business. In our experience, the issues that often undermine successful implementation, no matter how comprehensive the implementation framework, include:

- Underreporting - a tendency to water down the scale of issues as they are reported up the chain (e.g. moving red flags to amber) can be particularly problematic because it means that the board doesn’t actually have a true picture of events and the reality only comes to light when something disastrous happens.

- Siloed IT function - the “supplier” mentality that can often be observed in a siloed IT function can result in: (i) an unwillingness to report up the chain and/or a tendency to not trust other functions such as risk, compliance and audit; and (ii) a focus on targets, sometimes at the expense of what is best for the business as a whole (e.g. taking a ‘go’ decision to hit a deadline even where there remain some (potentially significant) risks or caveats, in particular where those are not properly articulated, reported or understood).

Expertise

Digital transformation projects involve increasingly new and complex technology and therefore require significant expertise.

One way to address this is to rely on external vendors. This is an increasing trend but one that comes with some potential pitfalls. While it has always been important to properly manage external vendors or third parties, it is now even more critical given their specialist knowledge.

To mitigate the risk of over reliance on vendors, organisations need to consider whether they have appropriate resources, capacity, skills, technical expertise and understanding of the technology throughout the organisation (including within the IT function, at board level and within the risk and audit function(s)) to support the governance, planning and testing processes.

It is important to consider and identify any gaps in resources, skills and expertise and how these can be best addressed (e.g., providing relevant training or adding external resources and/or expertise). Beyond the relevant tech knowledge, it is also important to ensure that those that are involved in the project understand the broader risks and legal/regulatory requirements, both through awareness of organisation-wide risks and requirements and, crucially, through clear, timely and meaningful reporting of issues and risks throughout the project.

Dealing with a tech meltdown

Sometimes, despite best efforts, things go wrong. How you react to the crisis will make a difference in how effectively (and how quickly) you are able to contain and, ultimately, resolve it.

Here are some of the key aspects to consider if you find yourself dealing with a tech meltdown.

Activate your crisis management framework but stay flexible. Your first step should be to activate any existing crisis response plan – but be ready to adapt to the specific facts of the incident if needed. Acting quickly is important but so is remaining flexible and adapting to the facts of the incident.

Be clear about the objectives and parameters of your investigation. As best you can at an early stage, determine the scope of the problem, including:

- an early indication of what caused the issue and why (e.g., a software update or a bug);

- any third-party service providers involved;

- systems and services that have been affected;

- how widespread the issue is and any cross-border element; and

- the time frame involved.

It is equally important to consider what is outside the scope of your investigation.

Build the right internal and external response team. Effective crisis management hinges on involving the right people. Close collaboration is key to understanding the technical failures at the heart of the incident.

- Identify and brief core internal stakeholders (key senior leaders and functional heads) who will need to oversee and manage the response.

- Establish a cross-functional investigation team, to investigate the root cause of the incident and assess its operational, regulatory, and reputational impact. The team should include a balanced mix of expertise (internal and external) and have a clear mandate, structure, and reporting lines to support effective and timely decision-making.

Communication is key. Consider both internal and external communication needs and requirements.

- Establish clear internal communication and reporting channels. In the initial stages, daily internal briefings can help maintain momentum, ensure alignment across teams, and provide decision-makers with timely updates.

- Assess and understand any legal or regulatory notification requirements (both on what and when needs to be reported).

- Document all key decisions, actions, and findings from the outset.

CYBER ATTACKS: A BOARD-LEVEL RESPONSIBILITY

Recent high profile ransomware attacks (including M&S, Harrods, JLR, Asahi and Coop) have highlighted a growing cyber risk, and the serious impact an incident can have on both:

- organisations - the costs to JLR of its ransomware attack are estimated at £1.9bn, making it the most economically damaging UK cyber event and resulting in the UK Government providing a £1.5bn loan guarantee; and

- the wider economy – the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (‘NCSC’) has recently reported a 50% increase in ‘highly significant incidents’ compared with 2024, with many disrupting UK essential services.

The NCSC’s annual review, published on 14 October, notes that the challenge organisations face is growing at an order of magnitude, and calls for “all business leaders […] to take responsibility for their organisation’s cyber resilience”.

In addition, the Government has recently written to chief executives and chairs of leading UK businesses (including all FTSE350 companies) highlighting the importance of government and business working together to protect the UK economy and make cyber resilience a Board-level responsibility.

As a result of the increased cyber risk (and high-profile nature of that risk) many organisations have increased their focus on cyber governance and their preparedness activities. But what steps should organisations take now?

- Follow the NCSC’s latest guidance around improving security posture:

As well as working to prevent attacks, organisations need to implement systems that operate and recover following cyber disruption. Established cyber security measures, such as business continuity and disaster recovery, will remain important in this regard. However, the NCSC also suggest that organisations look towards engineering fundamental resilience to improve their ability to recover and mitigate the impact of unexpected cyber incidents. This may include leveraging architectural and operational approaches such as chaos engineering (deliberately introducing failure to validate detection and recovery) and running critical business functions on duplicate but distinct instances (to ensure continuity of critical services). For more advice from the NSCS, see their annual review and toolkit for boards. - Understand your supply chain and the impact of an incident on them:

Supply chain risk is another key area of concern highlighted in the NCSC’s report. It recommends using a new tool developed by IASME that allows organisations to conduct searches across a large number of suppliers to find out whether they are certified to Cyber Essentials or Cyber Essentials Plus (the UK government backed certification scheme recommended as the minimum standard of cyber security for all organisations). While this will help protect against inbound supply chain risk (i.e. the supply chain being a weak link into an organisation’s systems), the recent JLR attack is also a reminder that organisations need to protect against the outbound impact of a cyber attack. Reports suggested that the disruption to production caused by JLR’s incident meant some of its supply chain were facing bankruptcy. See this blog for more information on how to protect against outbound risk. - Ensure preparedness planning covers a range of scenarios:

We help many clients with their cyber board training or senior management table-top exercises and discuss a range of issues and scenarios with them. For example, in addition to the important decision of whether an organisation can/should pay a ransom, boards often need to understand the importance of maintaining a co-ordinated and strategic comms plan (particularly given new regulatory incident notification obligations), the long tail of an attack and the implications of certain operational decisions such as whether and when to turn systems off (and back on). The recent Co-op attack is an example of an organisation which is reported to have taken their systems offline when they discovered the attack had started, which did not prevent data being taken by the attackers but did stop them deploying their ransomware.

|

Shirine Khoury-Haq |

NON-EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR REMUNERATION UPDATE

The Financial Reporting Council (“FRC”) recently published updated guidance on how UK-listed companies can remunerate their non-executive directors (“NEDs”) using shares in the company that engages them. This update forms part of a broader regulatory effort to increase London’s attractiveness as a listing venue (in particular when compared to the major US stock markets). The aim is to help companies attract high-calibre board members in the global market for talent while maintaining strong governance standards.

Overall, the updated guidance gives listed companies welcome flexibility. The FRC is striking a balance between giving companies the flexibility to remunerate NEDs partly in shares (and align NEDs’ interests with the shareholders they represent), and maintaining the independence needed for effective objective oversight of corporate activity. We are aware of a number of companies considering incorporating the use of shares into NED remuneration packages.

Under the new guidance, Boards may pay part of their NEDs’ fees in shares, provided the rationale for doing so and any restrictions on the shares are clearly disclosed. If companies offer NEDs options or similar rights to acquire shares, they should not be performance‑related or have a meaningful exercise price that could impair independence. As an overarching principle, any share-based remuneration structures should avoid incentivising short‑term decision‑making, creating conflicts of interest, or compromising independence. Listed companies who take up this increased flexibility would be expected to explain their approach in their annual report.

Practically speaking, this means that companies can deliver a portion of NED fees in shares and/or grant NEDs options or similar rights to acquire shares, which allow NEDs to participate in share price growth from the time those options/rights are granted. Under the revised guidance, companies can technically source the shares they deliver to NEDs either by using some of the cash fee paid to NEDs to purchase shares on the market, or by issuing new shares.

There are however certain technical (but not insuperable) hurdles that the company needs to address when remunerating NEDs with shares as NEDs are not employees and therefore do not benefit from the exemptions for “employee share scheme” awards from the company’s obligations under the Companies Act.

It is also likely that the company will need shareholder approval under the Listing Rules to deliver free share awards to NEDs, and potentially to amend the directors’ remuneration policy as well. The tax treatment of the arrangements also requires consideration, including a mechanism to allow NEDs to sell sufficient shares during any close period to discharge any tax liabilities that arise in connection with their share awards.

FRC PUBLISHES ANNUAL REVIEW OF CORPORATE REPORTING 2024/25

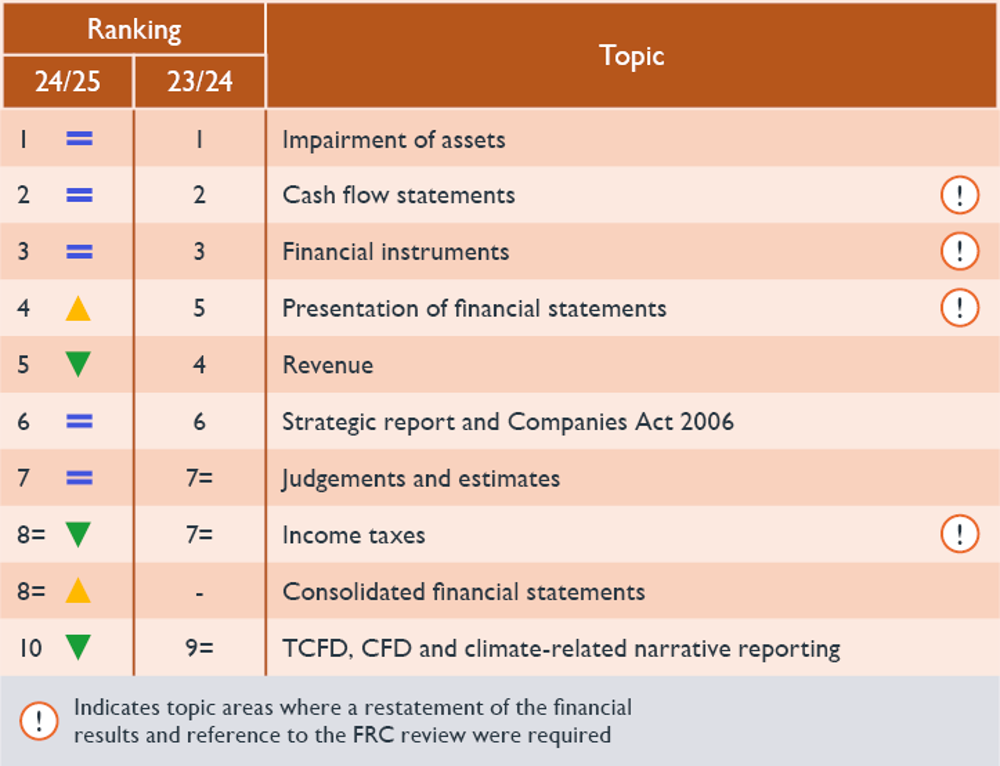

On 30 September 2025, the FRC published its Annual Review of Corporate Reporting 2024/25, outlining findings from its review of 222 annual reports (FTSE 350, AIM, and large private companies) during the year ending 31 March 2025 (FRC Press Release). The review highlights areas for improvement and sets expectations for the next reporting season.

Key findings

- Overall reporting quality among the reviewed FTSE 350 companies was maintained. However, there is a continuing quality gap between FTSE 350 and other companies; most restatements arose outside the FTSE 350. A thematic review of 20 smaller listed and AIM companies is ongoing and a report on this will follow later this year.

- Impairment of assets remained the most common issue. Clearer disclosures and better cross-referencing would have reduced queries.

- Cash flow statements generated the second-highest number of queries, mainly due to classification errors outside the FTSE 350.

- Inconsistencies between the financial statements and other report sections remain a significant trigger for queries.

- Explanations of significant judgements and estimates require improvement; geopolitical and economic risks increase uncertainty in estimates.

- There were fewer substantive questions on Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) reporting, which is in its third year for most listed companies.

Expectations for 2025/26 reporting

- Ensure coherent, clear, concise disclosures of all material and relevant information. Does the annual report and accounts as a whole tell a consistent and coherent story throughout the narrative reporting and financial statements? Include only material and relevant information – good quality reporting does not necessarily require a greater volume of disclosure

- Operate robust pre-issuance review processes to identify common technical compliance issues. Many questions and corrections could be avoided by reviewing against the top ten issues (opposite), including ensuring that clear, company-specific accounting policies are included for key matters such as revenue recognition.

- Provide clear, consistent disclosures on judgements, uncertainty and risk. These must be sufficient for users to understand the positions taken in the financial statements. The FRC frequently asks companies to enhance their disclosures when they fail to comply with requirements in these areas.

- Present a strategic report that is fair, balanced and comprehensive on current position and future prospects. Take care to comply with the applicable climate-related reporting requirements, ensuring disclosures are concise and that material information is not obscured.

Top ten areas for substantive queries

PROVISION 29 OF THE UK CORPORATE GOVERNANCE CODE 2024: WHAT NON-EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS NEED TO KNOW

The 2024 revision of the UK Corporate Governance Code (2024 Code) introduces a significant shift in how boards report on internal controls, with Provision 29 at its core. Moving beyond narrative disclosures, boards will now be required to provide a formal declaration on the effectiveness of material controls. Changes have also been made to Principle O, which make it clear that the board must not only establish, but also maintain, an effective risk management and internal control framework. This article explores the key requirements of Provision 29, the rationale behind its introduction, and the practical steps boards should take to ensure their companies are prepared for compliance.

What is Provision 29?

Provision 29 requires boards to:

- Monitor the company’s risk management and internal control framework.

- Conduct a review, at least annually, of its effectiveness.

- Disclose in the annual report:

- A description of how the board monitored and reviewed the framework.

- A declaration of effectiveness of material controls as at the balance sheet date.

- Details of any material controls that were not effective at that date, actions taken or proposed, and updates on previously reported issues.

This marks a shift from descriptive reporting on internal controls to requiring an affirmative declaration, extending beyond financial controls to include operational, compliance and (new in the 2024 Code) reporting controls. Provision 29 also requires a description of how the board monitored and reviewed the effectiveness of the framework, with the FRC expecting more detailed reporting on internal controls. These changes sit alongside changes to Principle O, which make it clear that the board must not only establish, but also maintain, an effective framework.

When does it apply?

Although the 2024 Code applies to listed companies on a ‘comply or explain’ basis from financial years beginning on or after 1 January 2025, Provision 29 has a delayed implementation date of financial years beginning on or after 1 January 2026. This means the first reporting under Provision 29 will appear in annual reports for 2026 year-ends, published in 2027. This delay provides companies time to prepare; companies will need to ensure that any additional processes and procedures are in place during the reporting period to ensure that the board has sufficient evidence to make the declaration of effectiveness and report on how it has monitored and reviewed the framework.

Why have these changes been made?

The FRC was invited by the previous Government to amend the UK Corporate Governance Code in order to strengthen board accountability and reporting in relation to internal controls. The amendments to Provision 29 are central to this in making clear the board’s accountability for effective internal controls. They form part of a wider set of ongoing reforms aimed at the corporate governance and audit framework in the UK.

How are companies preparing for these changes?

- Update the board and its committees on the changes: Ensure that the directors understand their new responsibilities under the Code

- Review and refine the internal control framework: Ensure the risk management and internal control framework is robust, fit for purpose and covers all material controls—financial, operational, compliance and reporting. Assess how risks are identified.

- Revisit principal risks and material controls: Reassess principal risks and redefine material controls accordingly to ensure focus remains on those most critical to the company’s resilience and stakeholder interests. Map principal risks against existing controls and identify any gaps.

- Document material controls: Confirm that material controls have been agreed and documented. These should be company-specific and reflect their impact on the company, shareholders and other stakeholders.

- Clarify information requirements: Determine what evidence the board needs to review the framework and make the declaration. Ensure relevant and timely information is being collected and shared.

- Assess assurance needs: Identify any additional internal (or external) assurance activities - such as testing or validation - required to support the board’s declaration.

- Plan for ongoing monitoring: Establish how the board will monitor the framework, including the effectiveness of controls, throughout the year, including the frequency and format of reporting to the board.

- Update committee terms of reference: Revise board committee terms of reference to reflect new responsibilities under the updated Code (this will usually impact at least the audit committee).

- Conduct a dry run: Trial the board declaration and enhanced disclosures ahead of the effective date to identify gaps and refine processes.

Conclusion

Provision 29 represents a clear call to action for the board to review, and where necessary refine, their company’s risk management and internal control framework. The move from narrative reporting to a formal declaration of effectiveness underscores the importance of proactive oversight and clear evidence-based assurance. While the delayed implementation offers valuable time to prepare, boards should not wait to act.

Non-executive directors should engage early with management and others to assess readiness, refine frameworks and ensure that monitoring and reporting mechanisms are fit for purpose. By doing so, boards will be well-positioned to meet the new requirements confidently and credibly, reinforcing stakeholder trust and supporting long-term resilience.

DIGITISATION OF SHAREHOLDINGS: THE ROAD AHEAD

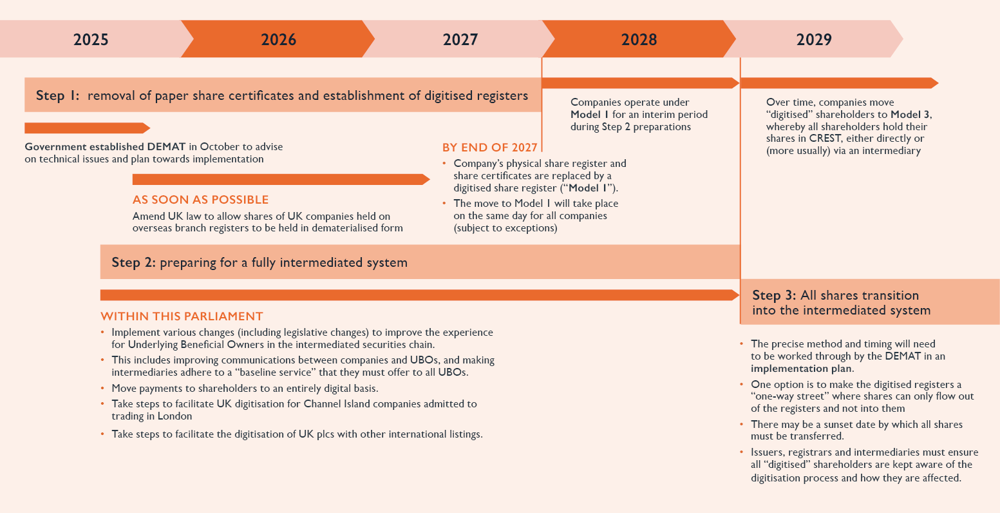

In July, the Digitisation Taskforce, led by Sir Douglas Flint, delivered its Final Report setting out its recommendations for modernising the UK’s share ownership framework in public companies. The government has accepted all the recommendations and in October it established the Dematerialisation Market Action Taskforce (DEMAT), to advise on technical issues and finalise the details for implementation.

The implementation of the proposals set out in the report is seen as important in modernising the UK’s financial markets, enhancing competitiveness with other markets that are already embracing full digitisation, and delivering growth in alignment with the government’s broader capital markets agenda.

The Taskforce has set out a three-step process towards full digitisation. This staggered approach has mainly been adopted to allow time for improvements to be made to the intermediated securities chain and ensure a baseline set of rights that underlying beneficial owners (“UBOs”) will continue to be able to exercise when they cease to be direct shareholders and transition to a fully intermediated system, as well to address certain other legal and other issues. Note that the recommendations are relevant for listed public companies only; the Taskforce recognised that for private companies, the proposals would not be cost-effective.

Step 1: Removal of paper shares and establishment of digitised registers

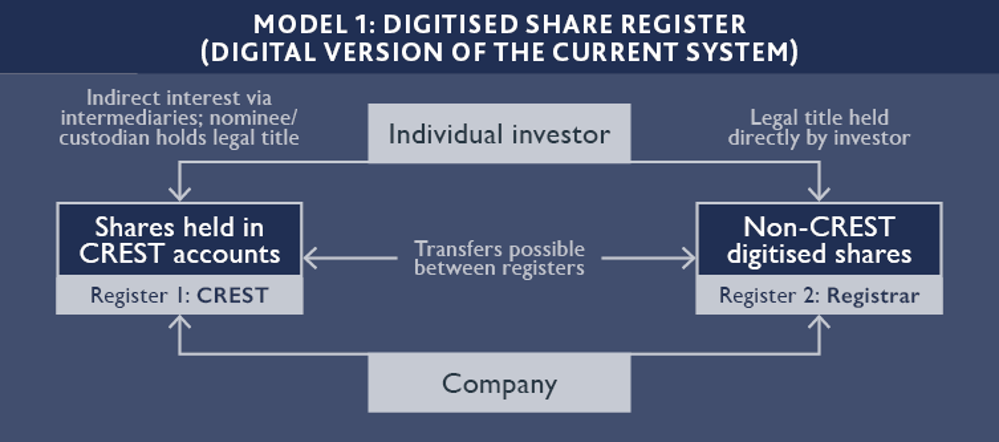

By the end of 2027, current paper share registers and share certificates will be replaced by digitised registers, replicating the service paper shareholders receive today but in digital form (what the Taskforce calls “Model 1”). Share certificates are nullified.

Step 2: Preparing for a fully intermediated system

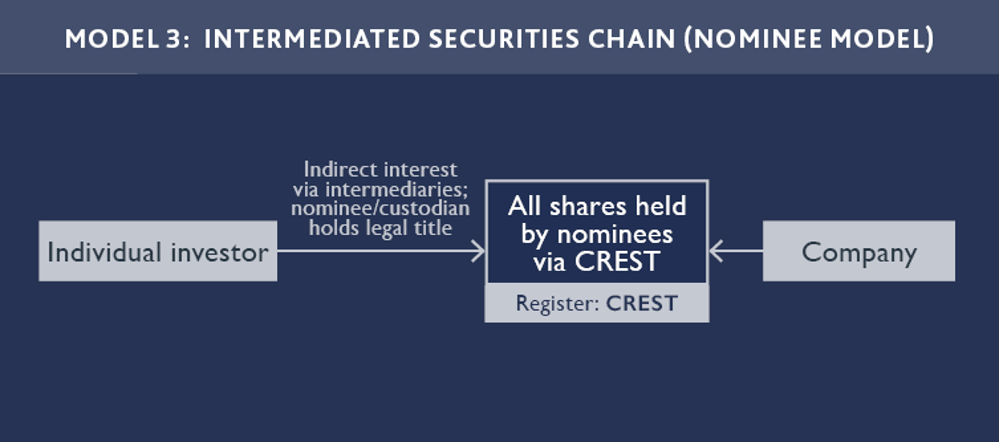

Companies will operate under Model 1 for an interim period while improvements to the intermediated securities chains and other legislative changes are made. The Taskforce recommends that Step 2 preparations be completed by the end of the current Parliament in 2029.

Step 3: All shares transition into the intermediated system

Companies will move all shareholders to a fully intermediated system (“Model 3”). Given that the Step 2 improvements will need time to implement, there is no definitive timeframe yet and DEMAT will prepare an implementation plan in due course. The move from Model 1 will likely be gradual and may involve making the digitised register a one-way street, so shares can only be transferred out of it, but not into it.

Taskforce's indicative timeline for implementing the final recommendations

(Click image above to view)

Why not move to Model 3 at once?

Although adopting Model 3 is the ultimate endpoint, companies will operate under Model 1 for an interim period. This staged approach has been taken principally because improvements are needed to the intermediated system before all shares can be transferred into it, to ensure that ultimate beneficial holders of shares can exercise their rights.

Current intermediated models can give rise to difficulties and delays in communicating information up and down the chain to the investor, or may not allow investors to determine how voting and other rights should be exercised. The Taskforce has made various recommendations to enhance the rights of ultimate investors to address these concerns and proposed a “Bill of Rights” (see box) that will act as a baseline service that intermediaries must offer all shareholders.

Respondents to the consultation also expressed concern about the disruption and costs involved in moving directly to Model 3.

In addition, there are particular issues for certain companies that need to be addressed before moving to Model 3. For a number of companies with overseas listings, Model 3 would be currently unworkable (notably companies with listings of shares in the US and Hong Kong) - for a mixture of legal, operational, regulatory and tax reasons.

Furthermore, there are particular issues for companies with overseas branch registers, notably in Hong Kong (including HSBC, Standard Chartered and Prudential). Improvements need to be made to the inter-operability of international settlement systems before moving to Model 3. The final move to Model 3 may be subject to a small number of exceptions for such companies if interoperability between central securities depositaries has not improved.

What does this mean for listed companies?

The proposals will largely be welcomed by listed companies. The current paper-based processes for issuing certificates and making payments, and for sending documents to shareholders who have opted to receive hard copies, lead to inefficiencies and costs. These costs are effectively subsidised by other investors.

The move away from two registers – a CREST register for dematerialised shares and a register for shares that are held in certificated (paper) form – to one single CREST register will also bring savings in the long run, although there will be an interim period where the company will continue to maintain two registers.

Companies will need to work with their registrars to put in place the necessary arrangements for converting the paper share register to a digitised register under Model 1. It is likely that any legislative changes to implement the proposals will be drafted so as to ensure that companies will not have to amend their articles of association in order to take advantage of the reforms. However, in due course, companies should consider updating them as a matter of good housekeeping.

Crucially, companies and registrars will also need to keep certificated shareholders informed about the changes. Some of the changes – including mandating shareholders to move to an intermediated system for which they will have to pay a fee (as opposed to the “free” service they receive as certificated shareholders) and moving all shareholders to electronic payments – raise PR implications that will need to be handled carefully, especially as certificated shareholders are proportionately more likely to be older.

|

The “Bill of Shareholder Rights” This sets out the Taskforce’s conditions that an intermediary’s baseline service to shareholders (including UBOs) must meet in order for it to be concluded that they are able to exercise their rights effectively and efficiently in the improved intermediated securities chain. |

|

|

1. Right to Receive Company Information Shareholders should be entitled to receive all relevant company information electronically, with the option to receive physical copies where necessary. |

4. Right to Transparent Fee Disclosure Shareholders should be informed of any intermediary fees related to identification, information transmission, and facilitation of shareholder rights. Fees should be non-discriminatory and proportionate to actual costs. |

|

2. Right to Transmission of Information through Intermediaries There should be prompt communication of company information through the intermediated securities chain to shareholders. Intermediaries should be obliged to transmit information about the identity of shareholders to the company, enhancing communication channels between the company and its intermediated shareholders. |

5. Right to Receive Payments Electronically Shareholders should receive payments electronically unless otherwise agreed with the company. |

|

3. Right to Participate and Vote Shareholders should have the right to participate and vote in general meetings, either directly or through intermediaries. They should be entitled to confirmation of vote receipt and assurance of valid recording and counting by the company. Shareholders should also have the right to know that their responses and instructions are transmitted by intermediaries back to the company without delay. |

6. Right to Seek Compensation for Misleading Public Information Shareholders should be able to seek compensation if they suffer a loss due to misleading statements, dishonest omissions, or dishonest delays in the publication of information related to publicly traded securities. |

If you would like more information on any of the matters covered, please do contact us, or speak to your usual Slaughter and May contact.

This material is provided for general information only. It does not constitute legal or other professional advice.